Washington, D.C., New York and Boston Showed Biggest Air Quality Improvements

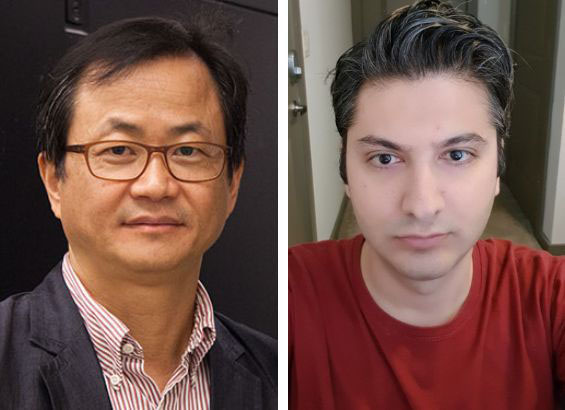

As vehicle traffic lightened and industry slowed during the COVID-19 stay-at-home period in 2020, a University of Houston study by the air quality forecasting group led by Yunsoo Choi, associate professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, estimates levels of potentially-dangerous air pollutants simultaneously decreased in major cities across the country.

All but one of the 11 U.S. cities examined experienced reduced levels of the pollutant PM2.5 — tiny particles or droplets in the air that are 2.5 microns or less in diameter. The negative health impacts of increased exposure to the pollutant include cardiovascular diseases, respiratory-related illnesses and similar conditions.

“We hope our study’s findings will provide insight useful to medical researchers and perhaps increase awareness of the need to explore cleaner energy alternatives,” said Choi, who is on the faculty of the UH College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics.

Using deep learning approaches, the researchers estimated and then compared PM2.5 levels from March through May 2020 — months when U.S. stay-at-home orders were tightest — to the same period in 2019. They also turned to Google’s COVID-19 Community Mobility reports, which temporarily reported anonymous data about traffic and destinations.

The biggest air quality improvement was in Washington D.C., which experienced a 21% decrease in pollution levels, followed by New York and Boston. The findings are published in the journal Atmospheric Environment.

Change in PM2.5 levels by city between March–May of 2020 and 2019:

- Washington DC, -21.1%

- New York, -20.7%

- Boston, -18.5%

- Detroit, -13.53%

- Chicago, -8.05%

- Seattle -7.73%

- Dallas, -6.71%

- Philadelphia, -4.82%

- Houston, -3.63%

- Los Angeles, -3.29%

- Phoenix +5.5%

Houston’s 3.6% decrease was among the mildest changes, a result the team attributed to the region’s many oil refineries and coal-fired power plant. “We need fuel, so the stay-at-home strategies did not impact oil refineries and power plants. Those facilities continued to operate and therefore continued to emit pollutants,” explained lead study author Masoud Ghahremanloo, a doctoral student at the University of Houston College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics.

In understanding Phoenix’s increase in PM2.5 levels — a 5% jump through the study period — the team noted that its residents had been more resistant to stay-at-home orders than most Americans, but they also found nature played a role, too.

“PM2.5 has many different ingredients — black carbon, organic carbon, nitrate, sulfate, dust, sea salt and so on. The natural ingredients — dust, sea salt and others — are not caused by industry or human mobility,” Ghahremanloo said.

Co-authors of the study from the UH Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences include doctoral students Yannic Lops, Jia Jung and Seyedali Mousavinezhad; and Davyda Hammond, project manager with Oak Ridge Associated Universities in Tennessee.

- Sally Strong, University Media Relations