Multi-institutional Genetics Study

The genome sequencing study, which was conducted by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) research network, provides the first comprehensive genetic overview of ovarian cancers, showing the changes that turn normal ovarian cells into deadly tumors that are highly resistant to chemotherapy. Researchers discovered that the ovarian cancer genome is overwhelmingly characterized by mutations in one gene and few other common mutations, but it also has frequent structural changes, indicating that those mutations are significant to the cancer's development.

Preethi Gunaratne, an assistant professor in UH's department of biology and biochemistry, is an author of the study, which is the largest such project to date conducted by TCGA, a network of institutions funded by the National Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institute of Health. Two other Houston institutions, Baylor College of Medicine and MD Anderson Cancer Center, also participated in the study, along with a number of others across the nation.

The findings could lead to better treatments for ovarian cancer, which claims the lives of nearly 14,000 women in the U.S. every year and is often not diagnosed until it's in an advanced stage.

"Ovarian cancer has been very difficult to treat. It has been very resistant to even the most advanced chemotherapy cocktails," Gunaratne said.

Gunaratne, along with Dr. Neil Hayes at the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina and Dr. Douglas Levine at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCCC), spearheaded the analysis of microRNAs, a class of tiny genetic molecules, to examine their role in causing and preventing ovarian cancer. The team's complete analysis of microRNAs in the TCGA study will be reported in a separate manuscript with contributions from Dr. Chad Creighton from the Dan Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor and Drs. Chris Sanders, Anders Jacobsen and Nikolaus Schultz at MSKCCC.

MicroRNAs were ignored as meaningless genetic material for a long time because they are too small to make proteins that can do anything important. In the last 10 years, these tiny molecules once dismissed as "genetic junk," have catapulted to occupy a central position in biology. Through the pioneering work of many researchers, microRNAs have been found to control 60 percent of the protein-coding genes in our genome.

"The power of microRNAs come from the fact that just one microRNA can bind, capture and silence hundreds of genes and, therefore, influence entire networks of genes," said Gunaratne, who has been at the forefront of this research.

The TCGA study found that 96 percent of the more than 300 ovarian cancer tumors analyzed had mutated TP53 genes, which normally are tumor suppressors. Even though this particular cancer has few other genes that are mutated, the structural changes were frequent. In the absence of the watchful eye of p53, these structural changes set the stage for the formation of aggressive tumors.

"This landmark study is producing impressive insights into the biology of this type of cancer," said NIH director Dr. Francis Collins. "It will significantly empower the cancer research community to make additional discoveries that will help us treat women with this deadly disease. It also illustrates the power of what's to come from our investment in The Cancer Genome Atlas."

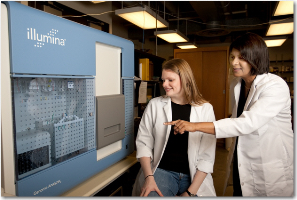

Gunaratne's team benefitted from the 2008 acquisition of a $1 million genome sequencer, a state-of-the-art device that made UH a major player in this pioneering research.

"I feel very lucky to have has access to the Illumina Genome Analyzer early. It gave us the opportunity to rapidly sequence hundreds of tumors to discover a valuable collection of potential tumor suppressor microRNAs for ovarian and a spectrum of other cancers," she said. "Because ovarian cancer has been particularly refractory to all current therapies and it remains the fifth- leading cause of cancer death in women and the most common gynecological malignancy, it is particularly exciting to see this project come to fruition.

Gunaratne said the next step for her team is to further develop the tumor-suppressor microRNAs discovered from this project and others in preclinical studies. The ultimate goal is to develop treatment therapies that can wipe out cancer-causing cells at very low doses of chemotherapy by exploiting the body's own silencing molecules such as microRNAs.

Gunaratne's work in ovarian cancer has gained substantial notice in the past year with a series of high-profile research grants, including a $200,000 High Impact/High Risk grant from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), which oversees the state's billion-dollar war on cancer. Late last year, she was chosen as one of the beneficiaries of the Baylor College of Medicine Partnership Fund, which takes on a major fundraising campaign each year for a specific health project. Earlier this year, Gunaratne was a co-recipient of the Virginia L.E. Simmons Family Foundation award with Texas Children's Cancer Center and the Texas Methodist Research Institute. Funds from the Cullen Foundation awarded to Gunaratne last year laid much of the foundation for this work.

- Laura Tolley, University Communication